Perfect number

In number theory, a perfect number is a positive integer that is equal to the sum of its proper positive divisors, that is, the sum of its positive divisors excluding the number itself (also known as its aliquot sum). Equivalently, a perfect number is a number that is half the sum of all of its positive divisors (including itself) i.e. σ1(n) = 2n.

Contents |

Examples

The first perfect number is 6, because 1, 2, and 3 are its proper positive divisors, and 1 + 2 + 3 = 6. Equivalently, the number 6 is equal to half the sum of all its positive divisors: ( 1 + 2 + 3 + 6 ) / 2 = 6.

The next perfect number is 28 = 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14. This is followed by the perfect numbers 496 and 8128 (sequence A000396 in OEIS).

Discovery

These first four perfect numbers were the only ones known to early Greek mathematics, and the mathematician Nicomachus had noted 8,128 as early as 100 AD.[1]

Then, in 1456, an unknown mathematician recorded the earliest reference to a fifth perfect number, with 33,550,336 being correctly identified for the first time.[2]

In 1588, the Italian mathematician Pietro Cataldi identified the sixth (8,589,869,056)[3] and the seventh (137,438,691,328) perfect numbers.[4]

Even perfect numbers

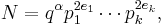

Euclid discovered that the first four perfect numbers are generated by the formula 2p−1(2p−1), with p a prime number:

- for p = 2: 21(22−1) = 6

- for p = 3: 22(23−1) = 28

- for p = 5: 24(25−1) = 496

- for p = 7: 26(27−1) = 8128.

Noticing that in each of these cases 2p−1 is a prime number, Euclid proved that 2p−1(2p−1) is an even perfect number whenever 2p−1 is prime (Euclid, Prop. IX.36).

For 2p−1 to be prime, it is necessary that p itself be prime. Prime numbers of the form 2p−1 are known as Mersenne primes, after the seventeenth-century monk Marin Mersenne, who studied number theory and perfect numbers. However, not all numbers of the form 2p−1 with a prime p are prime; for example, 211−1 = 2047 = 23 × 89 is not a prime number. (All factors of 2p−1 will be congruent to 1 mod 2p. For example, 211−1 = 2047 = 23 × 89 and both 23 and 89 yield a remainder of 1 when divided by 22. Furthermore, whenever p is a Sophie Germain prime—that is, 2p+1 is also prime—and 2p+1 is congruent to 1 or 7 mod 8, then 2p + 1 will be a factor of 2p−1.) In fact, Mersenne primes are very rare—of the 78,498 prime numbers p below 1,000,000, 2p−1 is prime for only 33 of them.

Over a millennium after Euclid, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) circa 1000 AD conjectured that every even perfect number is of the form 2p−1(2p−1) where 2p−1 is prime, but he was not able to prove this result.[5] It was not until the 18th century that Leonhard Euler proved that the formula 2p−1(2p−1) will yield all the even perfect numbers. Thus, there is a one-to-one relationship between even perfect numbers and Mersenne primes; each Mersenne prime generates one even perfect number, and vice versa. This result is often referred to as the Euclid–Euler Theorem. As of June 2010[update], 47 Mersenne primes and therefore 47 even perfect numbers are known.[6] The largest of these is 243,112,608 × (243,112,609−1) with 25,956,377 digits.

The first 41 even perfect numbers are 2p−1(2p−1) for

- p = 2, 3, 5, 7, 13, 17, 19, 31, 61, 89, 107, 127, 521, 607, 1279, 2203, 2281, 3217, 4253, 4423, 9689, 9941, 11213, 19937, 21701, 23209, 44497, 86243, 110503, 132049, 216091, 756839, 859433, 1257787, 1398269, 2976221, 3021377, 6972593, 13466917, 20996011 (sequence A000043 in OEIS), and 24036583.[7]

The other 6 known are for p = 25964951, 30402457, 32582657, 37156667, 42643801, and 43112609. It is not known whether there are others between them.

No proof is known whether there are infinitely many Mersenne primes and perfect numbers.

| Are there infinitely many perfect numbers? |

The search for new Mersenne primes is the goal of the GIMPS distributed computing project.

Because any even perfect number has the form 2p−1(2p−1), it is the (2p−1)th triangular number and the 2p−1th hexagonal number. Like all triangular numbers, it is the sum of all natural numbers up to a certain point; in this case: 2p−1. Furthermore, any even perfect number except the first one is the ((2p+1)/3)th centered nonagonal number as well as the sum of the first 2(p−1)/2 odd cubes:

Even perfect numbers (except 6) give remainder 1 when divided by 9. This can be reformulated as follows: adding the digits of any even perfect number (except 6), then adding the digits of the resulting number, and repeating this process until a single digit (called the digital root) is obtained, always produces the number 1. For example, the digital root of 8128 is 1, because 8 + 1 + 2 + 8 = 19, 1 + 9 = 10, and 1 + 0 = 1. This works with all perfect numbers 2p−1(2p−1) with odd prime p and, in fact, all numbers of the form 2m−1(2m−1) for odd integer (not necessarily prime) m.

Owing to their form, 2p−1(2p−1), every even perfect number is represented in binary as p ones followed by p − 1 zeros:

- 610 = 1102

- 2810 = 111002

- 49610 = 1111100002

- 812810 = 11111110000002

- 3355033610 = 11111111111110000000000002.

Odd perfect numbers

| Are there any odd perfect numbers? |

It is unknown whether there are any odd perfect numbers, though various results have been obtained. Carl Pomerance has presented a heuristic argument which suggests that no odd perfect numbers exist. All perfect numbers are also Ore's harmonic numbers, and it has been conjectured as well that there are no odd Ore's harmonic numbers other than 1.

Any odd perfect number N must satisfy the following conditions:

- N > 10300. A search has tentatively shown that N > 101500, but this result is as yet unpublished.[8]

- N is of the form

-

- where:

- The largest prime factor of N is greater than 108.[11]

- The second largest prime factor is greater than 104, and the third largest prime factor is greater than 100.[12][13]

- N has at least 101 prime factors and at least 9 distinct prime factors. If 3 is not one of the factors of N, then N has at least 12 distinct prime factors.[8][14]

In 1888, Sylvester stated:[15]

...a prolonged meditation on the subject has satisfied me that the existence of any one such [odd perfect number] — its escape, so to say, from the complex web of conditions which hem it in on all sides — would be little short of a miracle.

Minor results

All even perfect numbers have a very precise form; odd perfect numbers either do not exist or are rare. There are a number of results on perfect numbers that are actually quite easy to prove but nevertheless superficially impressive; some of them also come under Richard Guy's strong law of small numbers:

- An odd perfect number is not divisible by 105.[16]

- Every odd perfect number is of the form N ≡ 1 (mod 12), N ≡ 117 (mod 468), or N ≡ 81 (mod 324).[17]

- The only even perfect number of the form x3 + 1 is 28 (Makowski 1962).

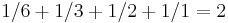

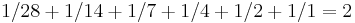

- The reciprocals of the divisors of a perfect number N must add up to 2:

- For 6, we have

;

; - For 28, we have

, etc. (This is particularly easy to see, just by taking the definition of a perfect number,

, etc. (This is particularly easy to see, just by taking the definition of a perfect number,  , and dividing both sides by n.)

, and dividing both sides by n.)

- For 6, we have

- The number of divisors of a perfect number (whether even or odd) must be even, because N cannot be a perfect square.

- From these two results it follows that every perfect number is an Ore's harmonic number.

- The even perfect numbers are not trapezoidal numbers; that is, they cannot be represented as the difference of two positive non-consecutive triangular numbers. There are only three types of non-trapezoidal numbers: even perfect numbers, powers of two, and a class of numbers formed from Fermat primes in a similar way to the construction of even perfect numbers from Mersenne primes. [18]

- The number of perfect numbers less than n is less than

, where c > 0 is a constant.[19] In fact it is

, where c > 0 is a constant.[19] In fact it is  , using little-o notation.[20]

, using little-o notation.[20]

Related concepts

The sum of proper divisors gives various other kinds of numbers. Numbers where the sum is less than the number itself are called deficient, and where it is greater than the number, abundant. These terms, together with perfect itself, come from Greek numerology. A pair of numbers which are the sum of each other's proper divisors are called amicable, and larger cycles of numbers are called sociable. A positive integer such that every smaller positive integer is a sum of distinct divisors of it is a practical number.

By definition, a perfect number is a fixed point of the restricted divisor function s(n) = σ(n) − n, and the aliquot sequence associated with a perfect number is a constant sequence.

All perfect numbers are also  -perfect numbers, or Granville numbers.

-perfect numbers, or Granville numbers.

See also

Notes

- ^ Dickinson, LE (1919). History of the Theory of Number. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington. pp. iii. http://www.archive.org/stream/historyoftheoryo01dick#page/4/.

- ^ Smith, DE (1958). The History of Mathematics. New York: Dover. pp. 21. ISBN 0-486-20430-8. http://books.google.com/books?id=uTytJGnTf1kC&pg=PA21.

- ^ Peterson, I (2002). Mathematical Treks: From Surreal Numbers to Magic Circles. Washington: Mathematical Association of America. pp. 132. ISBN 8-88358-537-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=4gWSAraVhtAC&pg=PA132.

- ^ Pickover, C (2001). Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 360. ISBN 0-19-515799-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=52N0JJBspM0C&pg=PA360.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Haytham.html.

- ^ "GIMPS Home". Mersenne.org. http://www.mersenne.org/. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ^ GIMPS Milestones Report. Retrieved 2011-12-03

- ^ a b c Ochem, P; Rao, M (2011). "Odd perfect numbers are greater than 101500". Mathematics of Computation 00 (000). http://www.lirmm.fr/~ochem/opn/opn.pdf. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Grün, O (1952). "Über ungerade vollkommene Zahlen". Mathematische Zeitschrift 55 (3): 353–354. doi:10.1007/BF01181133. http://www.springerlink.com/content/u6n2338x7mw10027/. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Nielsen, PP (2003). [An upper bound for odd perfect numbers "An upper bound for odd perfect numbers"]. Integers 3: A14–A22. An upper bound for odd perfect numbers. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Goto, T; Ohno, Y (2008). "Odd perfect numbers have a prime factor exceeding 108". Mathematics of Computation 77 (263): 1859–1868. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-08-02050-9. http://www.ma.noda.tus.ac.jp/u/tg/perfect/perfect.pdf. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Iannucci, DE (1999). "The second largest prime divisor of an odd perfect number exceeds ten thousand". Mathematics of Computation 68 (228): 1749–1760. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-99-01126-6. http://www.ams.org/journals/mcom/1999-68-228/S0025-5718-99-01126-6/S0025-5718-99-01126-6.pdf. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Iannucci, DE (2000). "The third largest prime divisor of an odd perfect number exceeds one hundred". Mathematics of Computation 69 (230): 867–879. http://www.ams.org/journals/mcom/2000-69-230/S0025-5718-99-01127-8/S0025-5718-99-01127-8.pdf. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Nielsen, PP (2007). "Odd perfect numbers have at least distinct prime factors". Mathematics of Computation 76 (260): 2109–2126. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-07-01990-4. https://www.math.byu.edu/~pace/NotEight_web.pdf. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ The Collected Mathematical Papers of James Joseph Sylvester p. 590, tr. from "Sur les nombres dits de Hamilton", Compte Rendu de l'Assoiation Française (Toulouse, 1887), pp. 164–168.

- ^ Kühnel, U (1949). "Verschärfung der notwendigen Bedingungen für die Existenz von ungeraden vollkommenen Zahlen". Mathematische Zeitschrift 52: 201–211. doi:10.1515/crll.1941.183.98,+//1941. http://www.reference-global.com/doi/abs/10.1515/crll.1941.183.98. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Roberts, T (2008). "On the Form of an Odd Perfect Number". Australian Mathematical Gazette 35 (4): 244.

- ^ Jones, Chris; Lord, Nick (1999). "Characterising non-trapezoidal numbers". The Mathematical Gazette (The Mathematical Association) 83 (497): 262–263. doi:10.2307/3619053. JSTOR 3619053

- ^ Hornfeck, B (1955). "Zur dichte der menge der follkommenen zahlen". Arch. Math. 6: 442–443.

- ^ Kanold, HJ (1956). "Eine Bemerkung ¨uber die Menge der vollkommenen zahlen.". Math. Ann. 131: 390–392.

References

- Euclid, Elements, Book IX, Proposition 36. See D.E. Joyce's website for a translation and discussion of this proposition and its proof.

- H.-J. Kanold, "Untersuchungen über ungerade vollkommene Zahlen", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 183 (1941), pp. 98–109.

- R. Steuerwald, "Verschärfung einer notwendigen Bedingung für die Existenz einer ungeraden vollkommenen Zahl", S.-B. Bayer. Akad. Wiss., 1937, pp. 69–72.

Further reading

- Dickson, L.E.: History of the Theory of Numbers, 1, Chelsea, reprint, 1952.

- Nankar, M.L.: "History of perfect numbers," Ganita Bharati 1, no. 1–2 (1979), 7–8.

- Hagis, P.: "A Lower Bound for the set of odd Perfect Prime Numbers", Mathematics of Computation 27, (1973), 951–953.

- Riele, H.J.J. "Perfect Numbers and Aliquot Sequences" in H.W. Lenstra and R. Tijdeman (eds.): Computational Methods in Number Theory, Vol. 154, Amsterdam, 1982, pp. 141–157.

- Riesel, H. Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorisation, Birkhauser, 1985.

External links

- David Moews: Perfect, amicable and sociable numbers

- Perfect numbers - History and Theory

- Weisstein, Eric W., "perfect number" from MathWorld.

- Sloane's A000396 : Perfect numbers. The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation.

- OddPerfect.org A projected distributed computing project to search for odd perfect numbers

- Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search

- Perfect Numbers, Math forum at Drexel

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

![\begin{align}

6 & = 2^1(2^2-1) & & = 1%2B2%2B3, \\[8pt]

28 & = 2^2(2^3-1) & & = 1%2B2%2B3%2B4%2B5%2B6%2B7 = 1^3%2B3^3, \\[8pt]

496 & = 2^4(2^5-1) & & = 1%2B2%2B3%2B\cdots%2B29%2B30%2B31 \\

& & & = 1^3%2B3^3%2B5^3%2B7^3, \\[8pt]

8128 & = 2^6(2^7-1) & & = 1%2B2%2B3%2B\cdots%2B125%2B126%2B127 \\

& & & = 1^3%2B3^3%2B5^3%2B7^3%2B9^3%2B11^3%2B13^3%2B15^3, \\[8pt]

33550336 & = 2^{12}(2^{13}-1) & & = 1%2B2%2B3%2B\cdots%2B8189%2B8190%2B8191 \\

& & & = 1^3%2B3^3%2B5^3%2B\cdots%2B123^3%2B125^3%2B127^3.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0a66bd56ba6dea1fc95634f6b53f9d56.png)